There are now 38 more dead Turkeys in the world. At 5:30 in the morning, Ross and I pulled on our coats and headed down the hill. We met Kirley and Ty (our fellow farm-workers) dressed in rubber boots; prepared for a messy day. We raised all our hoods, put on gloves and went bird-napping in the before-dawn dark. It is a surreal thing; approaching a flock of Turkeys out in a field, in the dead of night. It felt like doing something illicit, like we should have been wearing balaclavas. The first part of killing pastured Turkeys is catching them. One catches Turkeys by, well, grabbing them, sort of bear-hug style to keep them from flapping and scratching at you. Fortunately, they are more docile at night, though the first one Kirley caught went for her face with its beak. They are both heavy and strong, so sometimes, when I caught one, their sheer weight caused me to drop the beast. I tell you, it took some adrenaline to do it. There were no severe injuries, thankfully. We gently set each bird, individually into the livestock trailer. Only when there were three left did catching them become really difficult. They seemed to realise that their numbers had dwindled dramatically and that those birds that left did not seem to be coming back. We decided to grab all three of them pretty much at once to avoid a showdown, which more or less worked, except I lost my nerve and Kirley had to come grab my solitary, slightly panicked bird. Once we successfully loaded the turkey's we drove about forty minutes to Jamie's buddy Sean's house. He has a really great poultry processing facility in his yard that was completely worth the trip, especially considering that where we normally process is in plain view of where the elementary school children tour around the farm on a daily basis.

Sean is an interesting guy. He's tall, lanky, and his hair is balding but for a horseshoe of black ringlets that give him the slight appearance of a Hasidic Jew in carhart overalls. He believes in the most insane conspiracy theories, his wife is a bit of a Jesus-freak (but in a good, not-at-all-scary way), and I later found out that that pistol his five-year-old son, who was running around with his two-year-old sister playing cowboys with, was real. Despite these unnerving characteristics, Sean's a cool guy. He has a couple of Milking Devon's and Jersey's, both heritage breeds. When we got there, Sean was milking the Devon who was red, horned, and bad-tempered. Milking Devons were the first cattle brought to North America by the pilgrims. There's only about 400 left in the world. Sean sees the importance of preserving the genetics of an historical breed, so he raises a few. By the time we finished milking and had a cup of coffee, the scalder was hot enough to begin slaughtering and butchering.

Jamie, our fearless and very experienced leader, started the process. He grabbed a turkey by its feet. It flapped around for a minute. Really, I couldn't help admiring how beautiful they are in this contorted position; arching their back and neck in this lovely "S" shape, wings outstretched. He gently put the bird, head-first into a silver cone and reached in to coax the turkey's fleshy head out the bottom. With a knife I wished were a bit sharper, Jamie found the artery in the bird's neck, just below it's head, and slit it open. Jamie really was a master at this. The bird flapped and struggled minimally, and stayed fairly clean. Kirley went next. She had slaughtered chickens before, but was more intimidated by the turkeys. She wasn't altogether sure of herself, but bravely (and now I think I understand where the turn of phrase comes from) took a stab. Her inexperience showed, as did that of everyone else there who slaughtered except for Jamie. Their cuts were much less precise, which I think did hurt the birds, as well as caused them to struggle a lot more. I use struggle gingerly. It was difficult to tell if the bird was alive or dead when it flapped around (only once actually pulling itself out of the cone, which was difficult to watch). I was sure that it was a "chicken with its head cut off" type of reaction where the nervous system shuts down by erupting violently, but I questioned it, since every time Jamie killed a bird this did not happen nearly as much. I was the only one who chose to refrain from killing. Maybe it was lack of courage, but I rationalised that I wanted to watch, learn, and to try to get my head around the idea of killing and how to do it better. I also reasoned that I lacked access to a sharper knife, which I am sure makes the process less painful for the birds.

The way I understand it, the reason the slitting of thoughts with a sharp knife is the preferred method of slaughter is this: think for a moment if you have you ever been cut with a sharp knife, a really sharp knife. If so, you probably didn't notice right away. You probably saw blood before you ever felt pain. Now, think of a less common injury, that of massive blood loss. Most people who have experienced heavy blood loss describe the sensation as a kind of fading, a swimming in and out of consciousness, or a dreamy, light-headedness. The idea behind slaughtering animals this way is that it is relatively painless and because of blood-loss, death happens quite comfortably for the animal. But the whole time we were killing turkeys, despite these thoughts, I couldn't help but wonder if this concept of "giving death" anthropomorphises these animals too much. Pretty much everything we did to these birds was better, less painful, and certainly less gruesome than what happens to them in nature. I remember going out into the sheep pasture one morning and finding a dead sheep; it's head and shoulder twisted unnaturally and all its internal organs removed. And on another morning, feeding the turkey's one dead, nothing left but bones and feathers in a brown, rotting heap. Another Turkey was sick. It's wing had somehow been broken, and as it steadily became worse, its own kind pecked it and abused it until its head was a bloody, grey mess and Ty finally, mercifully snapped its neck. We are so concerned for the mercy of the animals we eat, much more so than nature ever is. I can't help but wonder if this is another way that we have separated ourselves from nature, or if it is somehow in our nature to be merciful and to not want to cause harm and pain.

So, with those thoughts in my mind, I resigned myself to the process of scalding, plucking, eviscerating, and packaging. In order to pluck a bird easily, you have to heat the skin in water to just the right temperature for just the right amount of time. The machine is kind of like a rotisserie that pushes the bird with a metal plate in and out of the hot water for several minutes. The stink of hot wet dead bird became quite rank after mere minutes. Then, you pick up the hot, wet, dead bird that, mind you dry, already weighs some 40lbs, and wet at least 10 more, and hoist it into the plucker. The plucker is a large, stainless steel barrel lined with rubber, carrot-shaped nubs. When you turn the plucker on, the bird whirls around inside and the nubs serve to pull the feathers out in some mystery of physics I don't understand. It's pretty intense, watching this animal flap about, neck broken, being removed of its feathers. Then we pulled them out onto a table, removed the feet and heads, split open its belly and removed its entrails. I did a lot of this. I think because at this point the animal was becoming food, and I just sort of resonated with it. It was systematic and fascinating. Then the birds were cleaned with cold water, bagged, weighed, labelled, and put in the chest freezer. It was sort of amazing, having something that was alive not half and hour ago now bagged up and in a freezer, utterly changed, even unrecognisable from its original state. The whole process for 38 birds took about eight hours, including an hour lunch break and clean up. I learned all kinds of amazing and miraculous things about bodies and biology. It was such a powerful thing to see a 5 gallon bucket of blood set out for a few hours. It coagulated into a jello-like substance that was thick and dark and beautiful. There were buckets of unusable entrails, heads and feet and lungs, translucent oesophagus's, and bright green bile; yellow, shining intestines all twisting and curving. We bagged up livers and gizzards that were purpley and iridescent. I know, it seems so gross when I say it here in writing, but I can't stress how mesmerisingly beautiful it was to see: like a mystery of creation all laid out plain and vulgar, but no less mysterious.

By the end of the day I wasn't sure if I would ever eat turkey again, mostly due to the smell, but also, in part, due to the fact that my hands had the sensory memory of the soft squish of lungs being dug out of rib cages. We were all bloody, smelly, and exhausted. As we were driving away, I couldn't help but feel like I had been initiated, not only into the farm and the very essence of farming, but also into a shared experience of the rest of the world. In this month's National Geographic, there's an amazing photo of men in Bangladesh slaughtering a cow in the street. It's blood arches in a spray as the beast falls toward the ground, the men assisting in its death. The caption below reads that the slaughter is celebratory, in honour of Id al-Adha, a Muslim holiday in honour of Ibraham's willingness to sacrifice his son, Ishmael, at God's request. The story, though differing in detail between the Judeo-Christian and Islamic versions, is read similarly in all three traditions. It is a story of ultimate devotion to the divine and unwavering supplication to the will of God. It also shows that obedience to God, though it my look grim and painful, is always reconciled with unanticipated mercy (remember, God stops Abraham at just the right moment). For Abraham and Isaac (Ibrahim and Ishmael) the horrible journey towards death, indeed a total willingness to both kill and to die without fear is rewarded with joy and relief in the form of a sheep, willing to die in Isaac's stead. Fundamentally, this story links sacrifice with celebration, death with joy. And so, Ibrahim's life-affirming sacrifice it is celebrated in the Muslim world with, what else but sacrifice. Animals are ritually and publicly slaughtered and shared among the poor.

The take home message is that animal slaughter is old, it is common, it is even elemental to human existence. It was so in the ancient world and is so today. Animals die so that people might live and this natural order is to be celebrated. It is perhaps difficult for us here in the safe, sterile comfort of the Western world to associate violence with happiness, but we must face this unassailable truth: death is life. Imagine for a moment the happiness a family must feel when they acquire a cow, sheep, or goat that they can use perpetually for food. An animal is a perpetual source because it regenerates itself in the cycles of life, birth, and death. This process is jarring to the uninitiated, (yet so many of us here in the US literally worship this process in the form of Jesus). Imagine for a moment the great physical pains of most of the world, both past and present, of just how dirty and foul it can get. We now, in this country, live in a kind of golden bubble. We have the privilege and indeed, luxury of constant and unwavering food supply. So many of us have the privilege of never seeing an animal die (to say nothing of seeing a human being die). So many have the privilege of spending only twenty-percent of our income on food. So many have the privilege of never bloodying our hands, never sullying them in the planting of seeds and harvesting of roots, of never having smelled the stench of dead things. In short, a great many of us have the privilege of never having to get dirty in order to live. But someone else, somewhere does have to get dirty, and too many of us have the privilege to ignore them. It is this division of people, clean and unclean: those who see death and are willing to die just as much as their food is, and those who think that separation from death is the way to life. This division I reject. So, I got to know death a little better through the sacrifice of 38 birds, 38 birds that will be used to celebrate our bounty, that will be used to remind us of how grateful we are, or perhaps, how grateful we should be, and that will remind us that gratitude is the deepest way we are happy.

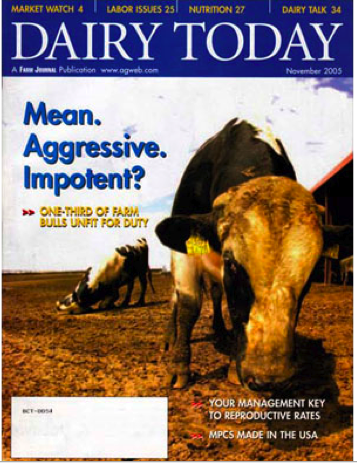

In this cover from 2005 we see a very straightforward design. No bells, no whistles. Really no design whatsoever. There are a few choice words on the cover that might, or might not entice you to buy this magazine. If you did want it, your reasoning would be purely cerebral. The image chosen is really what gets me: the dirty cows and insane perspective of filthy face-first bovine really peaks interest in the field of dairying, doesn’t it. I mean, come on! He looks like he’s ready keel over and die in a wasteland of mud and stink. Who’s for ice cream?! This kind of cover represents the standard of farming magazines, and to a large extent, farming in general. Ask the average person what farming is, ask what it looks like, what kind of work it is, and this is what you’ll hear: hard, drudgery, dirty, laborious, and gruelling with little reward. Indeed. And most farmers will tell you that that is not far from reality. There is, in farming, a kind of glorification of a lifestyle of self-induced poverty and satisfaction with the mediocre. I say self-induced because I do not believe that poverty and mediocrity are inherent traits of agriculture. Someone chose the image on Dairy Today, someone chose that typeface and those colours, someone chose to make it look so uninviting you would have to be desperate to want to take any interest in it. Worse still, this magazine’s appearance is either appealing enough or (more likely) totally irrelevant to the farmers who keep the magazine in publication. Ok, fine, maybe the articles are really good and that’s the attraction. But the point here is not the content of the magazine but rather, the content of an image presented of a dying and essential practice. The assumption of this cover is that one would not actively choose to farm unless it was the only option presented to you, or at best, there was some familial link that you take pride in. The point is that farmers are content to think of their profession as lowly. There is no desire to make it attractive, no desire to make it interesting to the average person, who, by the way, cannot live, that is live: breathe, work, play, make art, write songs, save lives, study aerodynamics or medicine, or literature, invent calculus and do all manner of worldly pursuits without farmers and farming. And farmers think of themselves as lowly, mediocre, humble? Can you imagine the panic if farmers were to go on strike? And you thought having to go without fresh episodes of SNL or Lost is rough. How can we ask people in this modern world, who take almost all of their food, sustenance, and means of survival for granted, to take pause and consider where their food came from and how it tastes when the farmers take themselves for granted?

In this cover from 2005 we see a very straightforward design. No bells, no whistles. Really no design whatsoever. There are a few choice words on the cover that might, or might not entice you to buy this magazine. If you did want it, your reasoning would be purely cerebral. The image chosen is really what gets me: the dirty cows and insane perspective of filthy face-first bovine really peaks interest in the field of dairying, doesn’t it. I mean, come on! He looks like he’s ready keel over and die in a wasteland of mud and stink. Who’s for ice cream?! This kind of cover represents the standard of farming magazines, and to a large extent, farming in general. Ask the average person what farming is, ask what it looks like, what kind of work it is, and this is what you’ll hear: hard, drudgery, dirty, laborious, and gruelling with little reward. Indeed. And most farmers will tell you that that is not far from reality. There is, in farming, a kind of glorification of a lifestyle of self-induced poverty and satisfaction with the mediocre. I say self-induced because I do not believe that poverty and mediocrity are inherent traits of agriculture. Someone chose the image on Dairy Today, someone chose that typeface and those colours, someone chose to make it look so uninviting you would have to be desperate to want to take any interest in it. Worse still, this magazine’s appearance is either appealing enough or (more likely) totally irrelevant to the farmers who keep the magazine in publication. Ok, fine, maybe the articles are really good and that’s the attraction. But the point here is not the content of the magazine but rather, the content of an image presented of a dying and essential practice. The assumption of this cover is that one would not actively choose to farm unless it was the only option presented to you, or at best, there was some familial link that you take pride in. The point is that farmers are content to think of their profession as lowly. There is no desire to make it attractive, no desire to make it interesting to the average person, who, by the way, cannot live, that is live: breathe, work, play, make art, write songs, save lives, study aerodynamics or medicine, or literature, invent calculus and do all manner of worldly pursuits without farmers and farming. And farmers think of themselves as lowly, mediocre, humble? Can you imagine the panic if farmers were to go on strike? And you thought having to go without fresh episodes of SNL or Lost is rough. How can we ask people in this modern world, who take almost all of their food, sustenance, and means of survival for granted, to take pause and consider where their food came from and how it tastes when the farmers take themselves for granted?

Hello, and welcome to the 21st century. Welcome to a world that has the ability to appreciate art and aesthetics, which, by the way, farming has a stake in. Look at this cow! She’s beautiful, she’s got personality, she’s got her tongue in her nose! And check out that typeface and setting. Wow. I love that the dot on the I of Dairy is the dot in the dot com of the website. How very edgy. Hell, I would pick up this magazine regardless of the articles. What do you see in this cover? Whimsy, maybe. There’s something about the baby blue here with the cow and the big Dairy at the top that makes me think ice cream cone. Plainly, this cover is sexy. It plays on eros: our desires. I desire this cow. I desire dairy products. I desire food. I desire to slip off the cover of this magazine and see just what’s inside. And hopefully, just maybe, I desire to look under the skirt of agriculture and see just where and how food is made. I mean, how different is it to ask how babies are made? Everything in agriculture is sexy. Come on, udders? How do you think those udders got so big and full of milk? Well, little Johnny, when a mommy cow and a daddy cow love each other very much. . . you catch my drift? Farming is all about reproduction, regeneration, and recreation. There is such joy in being a party to that process, such joy in being in a position to assist in and engender that process. Farming is not inherently unattractive, it is inherently attractive. This new cover is more telling of what farming actually is than the old one. And why not bring the inherent sexiness of farming into the bright light of day? We’ve been doing it with cooking for a good while now. Hell, my copy of Nigella Lawson’s cookbook Forever Summer depicts the author, beautiful and busty offering up a gorgeous clutch of round, red, ripe tomatoes. Food, not sexy? Huh? If there is an art of cooking and an art of eating, God Almighty, why not an art of farming? Look at that tongue!

Hello, and welcome to the 21st century. Welcome to a world that has the ability to appreciate art and aesthetics, which, by the way, farming has a stake in. Look at this cow! She’s beautiful, she’s got personality, she’s got her tongue in her nose! And check out that typeface and setting. Wow. I love that the dot on the I of Dairy is the dot in the dot com of the website. How very edgy. Hell, I would pick up this magazine regardless of the articles. What do you see in this cover? Whimsy, maybe. There’s something about the baby blue here with the cow and the big Dairy at the top that makes me think ice cream cone. Plainly, this cover is sexy. It plays on eros: our desires. I desire this cow. I desire dairy products. I desire food. I desire to slip off the cover of this magazine and see just what’s inside. And hopefully, just maybe, I desire to look under the skirt of agriculture and see just where and how food is made. I mean, how different is it to ask how babies are made? Everything in agriculture is sexy. Come on, udders? How do you think those udders got so big and full of milk? Well, little Johnny, when a mommy cow and a daddy cow love each other very much. . . you catch my drift? Farming is all about reproduction, regeneration, and recreation. There is such joy in being a party to that process, such joy in being in a position to assist in and engender that process. Farming is not inherently unattractive, it is inherently attractive. This new cover is more telling of what farming actually is than the old one. And why not bring the inherent sexiness of farming into the bright light of day? We’ve been doing it with cooking for a good while now. Hell, my copy of Nigella Lawson’s cookbook Forever Summer depicts the author, beautiful and busty offering up a gorgeous clutch of round, red, ripe tomatoes. Food, not sexy? Huh? If there is an art of cooking and an art of eating, God Almighty, why not an art of farming? Look at that tongue!

It has occurred to me recently, that of all the things that happen on this farm, the pigs seem to attract the most attention. Rarely do we ever discus how the cows did something crazy, or how the sheep kept us busy chasing them for hours. No, it’s all about the pigs. Pigs are prima-donnas. A case in point: yesterday evening, after a long day of fence-work, Kirley and I went to move the pigs. Sadly, a young pig had died in the back of one of the pig-houses. Less sad and more disgusting, it had not died recently. It’s crusty, wrinkly skin held what might have been jell-o squishing inside its bloated body. Need I bother to describe the smell? Ikk. Kirley, who was far braver than I (who wanted to go get a shovel and a wheel barrow), borrowed my gloves, grabbed onto its four feet, and carried it through the pig field and tossed it into a ravine. I would like to take this moment to let everyone out there know that Erin Kirley is amazing. After that, the two of us took the evening off early. I tossed my gloves into the washer with lots of bleach, cooked and ate pork ribs (the very recipe below), and thought to myself: it wouldn’t be worth it if they didn’t taste so damn good.

It has occurred to me recently, that of all the things that happen on this farm, the pigs seem to attract the most attention. Rarely do we ever discus how the cows did something crazy, or how the sheep kept us busy chasing them for hours. No, it’s all about the pigs. Pigs are prima-donnas. A case in point: yesterday evening, after a long day of fence-work, Kirley and I went to move the pigs. Sadly, a young pig had died in the back of one of the pig-houses. Less sad and more disgusting, it had not died recently. It’s crusty, wrinkly skin held what might have been jell-o squishing inside its bloated body. Need I bother to describe the smell? Ikk. Kirley, who was far braver than I (who wanted to go get a shovel and a wheel barrow), borrowed my gloves, grabbed onto its four feet, and carried it through the pig field and tossed it into a ravine. I would like to take this moment to let everyone out there know that Erin Kirley is amazing. After that, the two of us took the evening off early. I tossed my gloves into the washer with lots of bleach, cooked and ate pork ribs (the very recipe below), and thought to myself: it wouldn’t be worth it if they didn’t taste so damn good.