Yesterday, we made cheese. It was amazing.

Cheese Scoring

- 0: truly awful, why oh why did anyone ever make this? (pre-shredded, store brand, or generally poorly made: too much salt, too ammoniated, too propreonic, etc.)

- 1: Reasonable, overall unpleasant, but has some redeeming virtues, what I call "sandwich cheese" (a mediocre version of a standard cheese: Tillamook, etc.)

- 2: I don't like it, but I can see that someone else would. (Lumiere)

- 3: Good, solid standard D.O.P. cheese, par for the course, what you would expect (Parmigiano-Reggiano, Roqufort, Gruyere, Emmentaler)

- 4: Excellent, a very good, very nice cheese with unique and overall pleasant qualities, few complaints (Constant Bliss)

- 5: Supurb, really exceptional cheese, once I start eating, it can be hard to stop, great affection, no complaints (Bonne Buche, Green Hill)

- 6: Out of this world, mind-blowing, perfect in all ways, in line with personal and universal harmonies of flavour (Cashel Blue, Roaring Forties Blue)

Explanatory Note: this is just where I put things. I claim no universal cheese-tasting knowledge nor exceptional abilities. This system is just a tool to communicate what I like.

Shelburne Farm

Ross and I are up at VIAC this week finishing up some cheese chemistry courses. We took a most welcome field trip after class today to the beautiful Shelburne Farms. Let me preface by saying that the farm is located in an exceptionally beautiful area of Vermont along Lake Champlain. The weather also helped to greatly enhance the already-present beauty. Everything is this vibrant, living shade of green. The very wealthy or very lucky (perhaps both) have homes set on the hills, which gently roll into the Lake, framed by a view of the Adarondacks. The cool, bright afternoon was the antidote to a day spent sitting in a cramped, dim classroom looking at slides.

Ross and I are up at VIAC this week finishing up some cheese chemistry courses. We took a most welcome field trip after class today to the beautiful Shelburne Farms. Let me preface by saying that the farm is located in an exceptionally beautiful area of Vermont along Lake Champlain. The weather also helped to greatly enhance the already-present beauty. Everything is this vibrant, living shade of green. The very wealthy or very lucky (perhaps both) have homes set on the hills, which gently roll into the Lake, framed by a view of the Adarondacks. The cool, bright afternoon was the antidote to a day spent sitting in a cramped, dim classroom looking at slides.

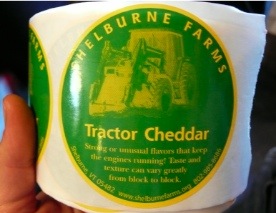

The Farm itself sits on 1,400 acres of Vanderbilt family land. It is committed to farm and education programmes that encourage sustainable agriculture, and according to their website, they aim, "to cultivate a conservation ethic in students, educators and families who come here to learn." Right up my ally. We went to meet their cheesemaker, Nat Bacon, and to see their facility. They milk 125 Brown Swiss ladies who are fed on pasture. They turn their milk into a variety of cheddar cheeses that are really nice. The facility is great: one huge, rectangular vat that can hold 3,000 pounds of milk, a couple of other make rooms, a packing room, and one gigantic aging room, and that's it. It was cool to see cheesemakers using the things we have been talking about at VIAC; the importance of pH and TA measurements, moisture and salt content, records, hygiene, the whole bit. Nat stressed record-keeping and how the chemical properties of the cheese affects how they plan to age the cheese and when they will sell it. It's such an intensive process to get a really good cheese and get it consistent in taste and texture every time that it really is impossible. From this necessary impossibility, Nat taught us an especially amusing and practical lesson in marketing. They make a cheese called "Tractor Cheddar":

The Farm itself sits on 1,400 acres of Vanderbilt family land. It is committed to farm and education programmes that encourage sustainable agriculture, and according to their website, they aim, "to cultivate a conservation ethic in students, educators and families who come here to learn." Right up my ally. We went to meet their cheesemaker, Nat Bacon, and to see their facility. They milk 125 Brown Swiss ladies who are fed on pasture. They turn their milk into a variety of cheddar cheeses that are really nice. The facility is great: one huge, rectangular vat that can hold 3,000 pounds of milk, a couple of other make rooms, a packing room, and one gigantic aging room, and that's it. It was cool to see cheesemakers using the things we have been talking about at VIAC; the importance of pH and TA measurements, moisture and salt content, records, hygiene, the whole bit. Nat stressed record-keeping and how the chemical properties of the cheese affects how they plan to age the cheese and when they will sell it. It's such an intensive process to get a really good cheese and get it consistent in taste and texture every time that it really is impossible. From this necessary impossibility, Nat taught us an especially amusing and practical lesson in marketing. They make a cheese called "Tractor Cheddar":

The label reads: Strong or unusual flavors that keep engines running! Taste and texture can vary greatly from block to block. The engine this cheese keeps running is the economic engine of the farm! This label demonstrates exactly how you sell your "mistakes" so as not to waste them. Sure, it's not going to win any prizes, but chances are that somebody out there likes your funky cheese, so why not keep the wheels of your operation turning as much when you fail as when you succeed? It's an interesting idea.

The label reads: Strong or unusual flavors that keep engines running! Taste and texture can vary greatly from block to block. The engine this cheese keeps running is the economic engine of the farm! This label demonstrates exactly how you sell your "mistakes" so as not to waste them. Sure, it's not going to win any prizes, but chances are that somebody out there likes your funky cheese, so why not keep the wheels of your operation turning as much when you fail as when you succeed? It's an interesting idea.

We spent the evening enjoying the formal gardens (with some HUGE hostas) around the inn and ate a lovely meal made from local meats, vegetables and cheeses from the farm, and excellent wine; all while we watched the sun set over the lake and disappear behind the mountains. What else is there?

Starting to Make Sense.

It's been seven, count them, seven months since I last wrote anything of substance. Inexcusable, I know. Especially when you consider how seven months ago I wrote the words, "You all will be hearing a great deal more about my teaching adventures in coming posts (which will be much more regular, henceforth)." Ha! But remember what else I said seven months ago, about how we're finding our way? Well, over the past seven months the way is finding its shape in some pretty awesome ways. We are shaping what we want to do with our lives here. It's no small potatoes and these things take time. Ross and I have been some incredibly busy bees with big, bright plans. Let's dive in, shall we?

It's been seven, count them, seven months since I last wrote anything of substance. Inexcusable, I know. Especially when you consider how seven months ago I wrote the words, "You all will be hearing a great deal more about my teaching adventures in coming posts (which will be much more regular, henceforth)." Ha! But remember what else I said seven months ago, about how we're finding our way? Well, over the past seven months the way is finding its shape in some pretty awesome ways. We are shaping what we want to do with our lives here. It's no small potatoes and these things take time. Ross and I have been some incredibly busy bees with big, bright plans. Let's dive in, shall we?

I will begin in January: On January 20th, two very important things happened: we got a new president, and I got to work. I watched the inauguration with some 20 high school students on my first day of my teaching internship. This internship is largely to blame for the long absence of posts. I've never done so much, so fast, in such a short space of time in my life. To call it draining would be an understatement. For 10 weeks I got up at 5:00am, taught three 90-minute class periods of English, finished up around 4:00pm, went to class twice a week until 7:00pm, and often did not get home before 9:oopm, in time to grade papers and revise lesson plans. Fun, right? I was exhausted by the end of it. The first thing Ross said to me when I finished was that I was never allowed to do anything like this ever again. He's right, and I won't.

Throughout my masters programme, I learned a huge amount about teaching, what children need in order to learn and grow, and they myriad ways they are and aren't getting those things. But what I learned about myself was equally important. I cannot work a "day job." The parameters of normal employment, and frankly working for someone else is simply not my cup of tea. I don't do well with other people's rules and expectations when those rules and expectations don't make any sense. It drains my spirit. I often joked during this internship that I was loosing the will to live; but really, it was only a half-joke. The moments I had with my students that really lit me up inside did not outweigh how sad and disheartened I am with the whole framework of how we educate. Don't misunderstand me, there are brilliant teachers and terrific schools; I am the product of both. But it seems to me that there are better ways. To put it more simply, in this programme I was handed the box and told how to get inside the box. I was not told how I might get out of the box and take as many kids with me as I could. . . which is what I want and what many of them need.

The point is, I came home every day and felt deflated, no matter how awesome the lesson went. Maybe I missed some key aspect of the art of teaching, maybe the skills to find they ways to love it every day in this context would come with practice over months and years, but I'm making other plans.

Sheep. Let's talk about them. Antoine de Saint-Exupery (yes, that Antoine de Saint-Exupery) said, "If someone wants a sheep, then that means that he exists." We agree. There is something about them that just feels good and right. Plus, they taste good, and more importantly, so does their milk: so we're gonna make cheese. When I start talking with folks about these cheesemaking plans, I typically get one of four reactions: 1)wow, that's awesome, I love sheep's milk cheeses! 2) You can milk a sheep?, 3) There are sheep's milk cheeses? or 4) Oh, so you're going make goat cheese! That's awesome!

In point of fact, the best cheeses in the world are made with sheep's milk cheeses (Roquefort, idiazabal, manchego, roncal, ricotta, feta, shall I go on?). Sheep's milk has the highest butterfat per litre content of any ruminant. Therefore, sheep efficiently turn grass into the highest quality of the stuff you need to make cheese with the least amount of waste (whey). Also, because of the high-quality and rich taste of most sheep cheeses, they fetch the highest prices. Plus, lamb, the natural by-product of dairying, is delicious.

At the advice of a fantastic cheesemaker in New York we met at ALBC a few years ago, Ross and I have been attending cheese school up at the University of Vermont's Institute for Artisan Cheese, meeting all kinds of farmers and cheesemakers, business planning, researching, and experimenting in the kitchen. We know a lot about milk chemistry now, and we're pretty darn excited about it.

However, at this point, I feel the need to add an explanatory note. A lot has been happening over the past few months and years that to an outsider, may seem like an odd trajectory; that somehow, Ross and I are scattered or directionless; winding along a meandering path of un-connected dots. All this, this is a winding road: me the medievalist and English major turned camp counselor for a wilderness school turned farm intern turned teacher, now writer, entrepreneur, farmer and cheesemaker; and Ross, who appears even more disconnected: the computer geek/ technical theatre buff/ urban designer/web-content consultant and trainer/farmer. Every time I tell my story to a passer-by I feel so self-conscious; I feel like I look scattered to them, directionless. Quite the opposite. I want to make good food, and I want to teach through that context. I want to think every day, make connections, solve tremendously complex problems, and remain, as ever, deeply intellectually and spiritually stimulated. And yes, this is a very medieval thing to do. My friend Brandon, an intern on the farm here for the year issued a similar complaint to my own. When he told one friend his story of how he came to want to be a farmer, the friend told him, "You are a polymath." For Brandon, that makes him feel, not directionless at all, it makes him, "feel like a farmer. "

Lately, I've been feeling a push to explain what I'm doing to folks, to somehow make my choices, hopes, and aspirations into something that makes sense to them. Really, the path I'm on, my way, it's mine, and to quote Brandon, "it makes sense to me."

Primitive Cheesemaking

We got our home cheesemaking equipment in this week and made the first attempt: queso blanco. The main part, cooking and chemistry, went well, but getting it into the press was quite an adventure. It's a Dutch‑style press, requiring a weight to exert force on the lever. Well, we lack any kind of “official” weight, so…

Read more