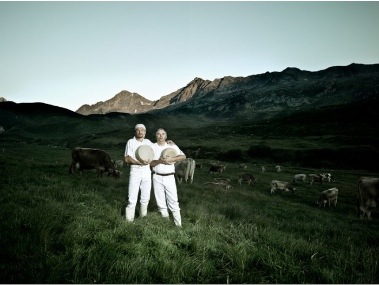

When most of us think of Swiss cheese we think of creamy, holey slices on our ham sandwiches. The truth is, Swiss cheeses are as diverse as cheeses anywhere else, coming in all shapes, sizes, forms, and textures. Most common are the traditional Alpine varieties that come in gigantic wheels of sweet, nutty, calcium-rich, deliciousness from which we in America have singularized into those "Swiss" sandwich slices. Recently, photographers Fabian Scheffold and István Vizner have been tromping around the beautiful Swiss countryside photographing these cheese makers. Their description of the cheese landscape in Switzerland sums up the attitude of most artisan cheese makers anywhere:

When most of us think of Swiss cheese we think of creamy, holey slices on our ham sandwiches. The truth is, Swiss cheeses are as diverse as cheeses anywhere else, coming in all shapes, sizes, forms, and textures. Most common are the traditional Alpine varieties that come in gigantic wheels of sweet, nutty, calcium-rich, deliciousness from which we in America have singularized into those "Swiss" sandwich slices. Recently, photographers Fabian Scheffold and István Vizner have been tromping around the beautiful Swiss countryside photographing these cheese makers. Their description of the cheese landscape in Switzerland sums up the attitude of most artisan cheese makers anywhere:

"The Book about Swiss Cheese Makers began as an editorial project for a journalist friend. " I expected this to be an agricultural trip, meeting people who make a living through the production of cheese in a more or less industrial way, " Scheffold confesses."But fare(sic) from it: I met unorthodox lateral thinkers, visionary fellows, modest canny and successful people living and working in some of the most spectacular landscapes of Switzerland. Some sell their products abroad, inventing a new cheese every other month, some work exactly as they have learned from their fathers, now sometimes just selling to hikers visiting their remote location by chance. But all of them seemed to follow an individual vision they are not willing to betray for growth and money."

I believe that this quotation is an example of an excellent and honest observation of the appeal of artisan cheese making and artisan farming in general (not just in Switzerland) and why so many young people are drawn toward it as a valid career option. We have become terribly jaded by the consequences of an endless pursuit of money. I recently watched the 1980's film Wall Street, made by Oliver Stone as a kind of modern morality tale about the perils of big money. Despite the creative intentions for the film, the reaction of most young, upstart business people at the time was that the film's villain, Gordon Gekko, was a hero, calling out to young businesspeople and showing them the unqualified pleasures of making gobs of money, regardless of the shady ways and shaky ethics this pursuit necessitates. I wonder now, though, in a world with Etsy in it and the New York Times doing pieces on people like this as real business, if Gordon Gekko's famous quotations would fly: "I don't create, I own."

With some, it probably always will, but it seems that the incoming generations are placing a higher value on the benefits of the qualitative aspects of life: a vision that is uniquely their own that attempts to define what a good product and process is over which product and process gives the most economic gain. There is a strong pull among young folks to create for a living over creating money in pursuit of owning for a living. Along with this notion comes the idea that a business is more than a money-generating enterprise. It can have multiple bottom lines. Businesses are accounting for triple bottom lines more and more, looking out for things like impact on people and environmental impact alongside profits. Multiple bottom lines can generate a variety of tangible and intangible values that the business creates and is responsible for; it is at once more complex and diverse than the simple profit bottom line, and yet can yield a drastic cut in the chaos of running a business. It can force it to slow down and can limit the business in helpful ways. In other words, multiple bottom lines can close doors to certain options, making the path that the business needs to take much clearer. One thing this means is that a business often has to be clear about how big it will get from the outset: when a business has unchecked growth it is often at the expense of either people, the environment, or both. We've seen the results of the illusion of infinite growth both in economics and in agriculture. It ends in disaster. That an entrepreneur and business person can draw a hard line about how big his or her company can grow and still be hugely successful and economically viable isn't a new thought in America, but the increased traction is. And it's encouraging. Let's hope we can all become Swiss cheese makers.

With these thoughts in mind, I leave you with a lovely piece from the website Civil Eats, the Young Farmer's Manifesto:

Many of us never meant to become farmers. We had ambitions to enter the world as accountants or lawyers or teachers or some other clean, respectable professional. We never really thought about the origins of our food; we always knew that the supermarket shelves would fill themselves, that food came in boxes or cans ready to serve and that farmers were simply one dimensional photographs in the mix of a hot new marketing campaign.

Farming was at best some idyllic retirement scheme, never a seriously considered career possibility.

But then something happened. In the previously steady route of our lives, a shift occurred. The soil moved under us somehow, got stuck in the creases of our pants, in the ridges of our shoes, in the lines of our palms. Suddenly white picket fences, situation comedies and mutual fund returns didn’t seem so interesting anymore…(Read More)

The Mad Farmer Liberation is happening…