Over the past few weeks, we have been selling eggs from our wonderful chickens to the community around our farm. We've used several outlets, including selling at a local CSA pickup location, our local farmer's market, our own CSA subscription program, a few dozen to our fabulous local farm-to-table restaurant, the Hil, most recently at the East Atlanta Village Farmers Market, and on a call-us-if-you-want-some-and-we'll-drop-them-off-for-you basis. The eggs we have been selling thus far can be classified as "pullet eggs" meaning that they are the eggs from immature, adolescent chickens. These eggs are of irregular, and often smaller size, and have other irregularities, such as double yolks. While the majority of folks have been really happy with their eggs, we've had a few balkers. Some don't love the small size, while others don't love the large price (we sell our eggs for $6, retail). Being someone who aims to please, I've considered how I could alter the price of my eggs to be more agreeable to these customers. I could compromise and stop buying organic feed, I could not sell my pullet eggs and simply wait for the size to become more regular or otherwise sell them for a lower price. However, I cannot, with good conscious, do these things. Sure, there is a point where you have to put your ideals aside for the benefit of the business, however, in my case, I simply can't afford to sell my eggs for less, and furthermore, most of my customers appreciate these eggs, both for their overall quality, as well as for the benefit of supporting a small, sustainable farm.

There was a week there where I fretted a lot about the eggs. I had a pretty serious backlog of unsold eggs. I've got my local CSA customers, whom I love and have allowed me to see first-hand the real benefits of the CSA model. However, I had several bad days in a row at my local farmer's market, the worst of which I sold only five dozen in three hours. Right now we're getting about 35-40 dozen per week from our 145 or so hens. Chickens take a while to get to the point where they are all laying every day, and in the record heat we've been having, it takes even more time. I knew that if I couldn't sell them all now, what on earth was I going to do later? I frantically began searching for other options, trying to figure out what I could do to either entice the customers I had further, or to get more of them.

The answer to my woes came, as so often it does for many of us young Georgia farmers, in the form of Judith Winfrey of Love is Love Farm. Judith is our very own rock-star farmer, food activist, leader, and general liaison to anyone and everyone in the farm-to-table world in Georgia. She answered my Facebook shout out looking for a farmer's market that was looking for eggs. Judith manages the super-duper-awesome East Atlanta Village Farmer's Market, where I have been selling out of eggs at my $6/doz price every week.

Having successfully crossed my first business hurtle (thanks to the powers that be that it was a small one!), I got to thinking more seriously about the value of food, and specifically, what an egg is worth.When I discussed egg pricing with Judith, she said that she's stood by Love is Love's $7/dozen price, despite the turned-up noses. She said, "I guess people really are getting to know the true cost of food." She's right, I think, and there's a fair few of them who aren't happy about it.

Recently, Time Magazine published an article based on a USDA study that showed that an organic egg was not appreciably different from a regular, industrial egg, and thus asserting that the price difference is bunk. However, what Time Magazine fails to mention is the tools the USDA used to measure egg quality in its study, the Haugh Unit. This tool is used to measure the physical characteristics of an egg, primarily with regard to freshness (the height of the albumen directly correlates with freshness). Of course, almost all eggs, industrial or organic are no more than a few hours to a few days old when they are graded. They are therefore, always fresh at the time of grading and get to bear the Grade A stamp (provided they have a reasonably uniform shell, and show a white and an in-tact yolk when candled), no matter how fresh they are by the time they arrive at your supermarket. Infuriatingly, the Time article also asserts that factory farm eggs are "safer" than organic eggs 1) without siting the claim, and 2) without noting that the organic eggs in a grocery store are industrially produced as well, and are therefore subjected to the same standards and regulations as non-organic factory eggs. One article I came across in responce to the Time article works to redress the mis-measurement of organic eggs and, quite rightly, asserts that the Haugh Unit is not a measure of nutritional value. While I applaude this, I can't help but think that there is some real value in debating the differences, nutritional and otherwise, in a typical industrial egg and an industrially-produced organic egg. This value is not just for the sake of debate, but really and truly because I do not believe that the differences are in fact appreciable and I think that is something worth exploring and pointing out.

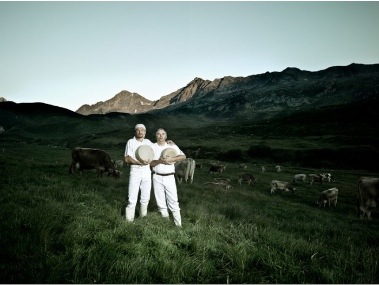

What neither the Time article nor the USDA research address is the existence of small-scale producers who direct-market their eggs, many of whom manage their hens on pasture. Pasture, folks, not "free range" and not "Organic". "Free Range" has a specific USDA definition that in no way includes grass nor guarantees that the birds will actually find their way outside. "Organic" likewise, has a specific USDA definition that primarily addresses the feed and drugs given to an animal. A pasture-raised hen actually lives on fresh, green grasses with access to sunshine and insects that she wants to leave her nest box to enjoy. If she eats a certified organic feed to supplement her intake on pasture, all the better for the health of your chickens and your customers who can be assured there is not chemical residues or other funky stuff in their eggs. I am stunned at the fundamental lack or research going into showing the public that it is this, this egg which you can ONLY get (as far as I am aware) directly from a farm, farmer's market, or supermarket that has a direct relationship with such a farmer, is not only ethically superior, but a nutritionally superior product.

Studies from the Journal of Nutrition and the Journal of Animal Science point in this direction, but unfortunately, only publications such as Mother Earth News (while wonderful, it is not scholarly and not widely read by nutrition "experts") have published anything that seeks to find direct links. We have to understand that until the USDA starts to look at an egg from a nutritional standpoint and conducts the research that will allow it to have real nutritional data on different egg production methods, we will be stuck with, frankly, lame comparisons of "freshness" of eggs laid in one style of factory farming versus another style of factory farming. The really good egg, unfortunately, gets left by the wayside while customers are left unaware of the real value of their egg.

Michael Pollan, in a recent Wall Street Journal interview, lays it out plainly:

We've been conditioned by artificially cheap food to be shocked when a box of strawberries costs $3.

But it's important to know that farmers aren't getting wealthy. When you see strawberries being sold for $1 a box, picture the kind of labor it takes to pick those strawberries and the kind of chemicals it takes to produce those kinds of strawberries without hand weeding.

Eight dollars for a dozen eggs sounds outrageous, but when you think that you can make a delicious meal from two eggs, that's $1.50. It's really not that much when we think of how we waste money in our lives.

What is artificially cheap food? Food that is subsidized. A single egg may cost $0.50 to produce (which is what ours cost), but when you start feeding them corn that is subsidized and providing housing that is subsidized, and drugs that allow them to live in cheap conditions that are subsidized, and disposing of the toxic waste chickens produce in an industrial setting that we don't pay for, you have a veritable cornucopia of costs that you and I, taxpayers, cover that I promise you, ends up being more than $0.50 an egg. I recently had a conversation with Owen Masterson (of GROW!) where we thought somebody out there needs to do the research (or if it's been done, let us know where), add up all the costs, and let us all know what an industrially-produced egg actually costs. It would be powerful, powerful knowledge.

Last week at market, I watched a woman with three young children pay for grass-fed steaks and ground beef with food stamps. I wanted to cry with joy. Some folks might be annoyed. They'd say this woman could get a whole lot more food for that money if she shopped at Kroger. But hold on a moment my fellow taxpayer and let us ask: how much more? What kind of more? More calories? Probably. Probably in the form of processed sugar and refined carbohydrates, leading her and her children a few steps closer to obesity. The meat she would be purchasing at Kroger would certainly be corn-fed, contributing to heart disease and other serious degenerative illnesses linked to corn-fed beef consumption, and because it's cheaper, she could buy more of it, filling bellies a little longer now, and costing thousands in healthcare and suffering later.

And so I implore you, farmer's market shoppers, when you're at market, buying good, clean, and fair food for your family, realize that, unlike the supermarket where you're paying very little for a whole lot of bad stuff (yes, even if you're buying organic), you're paying a little more for a lot more of the good stuff.

A quick update: Take a look at these stats from today's New York Times. My favorite part of the article is, "Many people don't approve of cage confinement, but they're 'basically asking for the cost of their food to go up' said George L. Siemon, the CEO of Organic Valley Farmers cooperative, 'you're not going to produce eggs that sell for $1.50 a dozen without cages." Indeed, Mr. Siemon, customers are asking for the price of their food to go up. It seems, contrary to the designs of industrial agriculture, that the consumer is in fact motivated my more than cost.