I don't even really know where to begin as I write this. Perhaps the beginning is best. In March, Ross and I attended the Georgia Organics annual conference. It was an amazing event filled with workshops, networking sessions, fantastic food, and Michael Pollan as the keynote speaker. All and all it was a very stimulating weekend, however, the most important information I got while there was a bit of advice from Dennis Stoltzfoos of Full Circle Farm in Live Oak, Florida. In his session on disaster-proofing your farm via mob-grazing to stimulate the creation and proliferation of organic matter on your field, he said simply, "take the time and the money and go see the master, it's worth the investment," the master being Joel Salatin. Some of you are thinking "what the heck is she talking about here? Mob-grazing, organic matter, Joel Salatin? What is all this?"

I don't even really know where to begin as I write this. Perhaps the beginning is best. In March, Ross and I attended the Georgia Organics annual conference. It was an amazing event filled with workshops, networking sessions, fantastic food, and Michael Pollan as the keynote speaker. All and all it was a very stimulating weekend, however, the most important information I got while there was a bit of advice from Dennis Stoltzfoos of Full Circle Farm in Live Oak, Florida. In his session on disaster-proofing your farm via mob-grazing to stimulate the creation and proliferation of organic matter on your field, he said simply, "take the time and the money and go see the master, it's worth the investment," the master being Joel Salatin. Some of you are thinking "what the heck is she talking about here? Mob-grazing, organic matter, Joel Salatin? What is all this?"

What it is, is everything.

Soil. Black, dirty, dirt. Organic matter is the thing Stoltzfoos kept coming back to in his talk. Every question he seemed able to answer with the magic words "organic matter." I watched farmer's eyes widen as they shook their heads. The answer to so many of their problems was just so simple and staring them in the face. Common modes of raising livestock typically include spraying herbicides to keep weeds at bay. Farmers pay to deworm their animals. They buy fertilizer to keep the grass growing. In times of drought, they sell off every last steer to a feedlot. But through the proliferation of organic matter on a field, a farmer will see higher yields and fewer gray hairs. Organic matter will hold water like a sponge, virtually drought-proofing your fields, improved nutrient cation exchange capacity, no tillage is needed to maintain it, it maintains the nutrient content of grass at a high level, it can keep you from buying hay, from buying fertilizer, from getting sick animals, the laundry list can go on and on. The question is, how do you get this good stuff and, more importantly, how do you get it where it needs to go.

Poop. Poop is perhaps the most prolific source of organic matter we have, and yet all we seem to do is throw it away. Farms have tons of the stuff. A cow sheds around 50 pounds of poop per day, nearly all of which sits on the ground, dries out, and washes away with a couple of rains (or else washes into a toxic lagoon near the feedlot). Meanwhile, a farmer might spend $15,000 or more on fertilizer in a year. So you see the conundrum. Farms would benefit from organic matter, they have plenty of access to it, but are unable to incorporate it into existing soil so that the nutrients don't disappear. So, they buy-in fertilizer because they can think of no better way to keep the grass growing and the cows fed.

Not Joel Salatin.

Salatin solves the problem of the need for fertility and organic matter through two simple and yet ingenious ideas: mob-grazing and chickens. Imagine for a moment that you are watching the Discovery Channel. You are watching a program about the sub-saharan plains, there are images of lions, elephants, giraffes, and wildebeest, or perhaps water buffalo. Now the herbivores in this scene, the wildebeest and water buffalo in particular, have another creature that likes to hang out with them: birds. What are those birds doing there? They're eating. They're eating all the bugs and grubs and worms that love to live in poop. How do they get to these tasty morsels? They take the poop and rifle through it, scattering it about until they've found every last little larvae therein. Now imagine the vast landscape of the African plain. Imagine the herds of wildebeest, of water buffalo, of zebras and antelope moving across that plain. How are they moving? Are they scattered all about? No. They stick together. Do they wander back over to the grass they've just eaten when there's plenty of fresh right in front of them? No. They always move forward, never returning to where they've just eaten. What we have observed in our imagined Discovery Channel documentary is the very thing that is the secret to healthy soil, prolific grasses, and in short a sustainable, zero-input system that actually enhances fertility and regenerates life. Joel Salatin has made to mirror this exact system with domesticated cattle and chickens.

Now, the concept of rotational (keeping animals from eating the same grass twice at the same time) and mob-grazing (giving animals many small sections at a time) has been around for a while. Really, the credit for the idea goes to a Frenchman, Andre Voisin who cooked up the concept of rotational grazing, and South-African farmer Ian Mitchell-Innes, who expanded Voisin's idea into mob-grazing. I also have to give credit to the New Zealanders, who took these ideas and ran with them, creating a wealth of models and equipment for these techniques. Salatin (along with the amazing Greg Judy, Allan Nation, and others) has taken these ideas one step further. Salatin does not let his cows have the entire pasture in one go. Instead, he gives them small sections at a time (with the use of temporary fencing) and moves them onto a fresh section every day. The cows do not return to that section for several weeks to several months. Then, three days later, the chickens roll in. Literally. Eggmobiles, filled with a couple hundred chickens pour out onto the field and start clawing and scratching and pecking their way through the cornucopia of cowpies. These birds kill parasites and flies, fertilize (both in spreading cow manure and in depositing fresh chicken manure), and create another low-input means of income: eggs, which come from chickens who eat 70% of their diet from the goodies in the field. All this is accomplished in one fell swoop.

(eggmobiles in action)

(eggmobiles in action)

Now you can begin to see why Stoltzfoos called Salatin "the master". But it doesn't stop there. Every enterprise on Salatin's farm is set up to mimic natural processes, or to use his term, halons, conveying the idea of interlinked, stacked circles. I can go on and on about the awesomeness of what he does and has created. I highly recommend reading up on his website, and anything he has ever written is well worth reading. Indeed, most folks have heard of him in Michael Pollan's book, The Omnivore's Dilemma, where you can get a terrific description of what Salatin does and a sample of the deep philosophy and political resonances of his work.

(Joel's herd)

So, long story short, we took Mr. Stoltzfoos' advice we went for a visit. Acres USA puts on two intensive workshops with Joel each summer. Early on a Friday morning, around thirty people came rolling up to the farm, ourselves included, ready to meet the man, myth, and legend. Now, I had heard a lot about Joel through the grapevine, not only about his ingenious practices, but a lot about his personality. I was beginning to get the impression that he was some kind of religious zealot with unwavering opinions about pretty much everything, who, despite being a great farmer, was arrogant and backwards in his social attitudes. This estimation could not be farther from the truth. Now I can see if all you've ever known about Joel Salatin is from his books and articles, you could begin to develop a negative view of him. He's strong-minded, doesn't namby-pamby around, and speaks authoritatively; as if he's absolutely convinced he's right. Apparently, some folks find that tone off-putting, but the fact of the matter is that he's passionate, he's blunt, and he is usually right. Joel is someone who has to be taken as a complete package. When you hear him speak, he speaks his mind and he speaks his truth; his tone is passionate, and with that passion comes an authority of opinion. One sees upon meeting him, however, that surrounding that fire is a pure kindness. Joel Salatin is far and away one of the kindest souls I have ever met. His family and the folks that work with him are equally kind. Never had I experienced such hospitality, especially in a group: smiles, favors, and a general sense of absolute ease. I think that part of the kindness that exudes from Joel and everyone around him is a genuine respect for all living things. Joel calls himself a "caretaker of creation" and he takes that role unbelievably seriously. Joel understands the place of every blade of grass, flower, worm, maggot, bacteria, fungi, chicken, cow, tree, newt, dog, rabbit, corn, bean, bee, pig, and person on his land and therefore respects each one in kind. He knows that no one thing can function without the other: without the maggots, the chickens would have one less thing to eat, without the chickens, his cows would get sick, without the cows, the fields would suffer and plants would die, worms couldn't eat without the cows or chickens and so they could not enrich the soil that feeds the cows and chickens, and then people couldn't eat either, and without the people who would do all this important work? Who would create these systems that mend the land, and without these 30 visitors, who would there be to continue the work? He sees humans as co-creators with God, who work not only to sustain the land and the life it supports, but to improve it, to regenerate it.

(Joel's herd)

So, long story short, we took Mr. Stoltzfoos' advice we went for a visit. Acres USA puts on two intensive workshops with Joel each summer. Early on a Friday morning, around thirty people came rolling up to the farm, ourselves included, ready to meet the man, myth, and legend. Now, I had heard a lot about Joel through the grapevine, not only about his ingenious practices, but a lot about his personality. I was beginning to get the impression that he was some kind of religious zealot with unwavering opinions about pretty much everything, who, despite being a great farmer, was arrogant and backwards in his social attitudes. This estimation could not be farther from the truth. Now I can see if all you've ever known about Joel Salatin is from his books and articles, you could begin to develop a negative view of him. He's strong-minded, doesn't namby-pamby around, and speaks authoritatively; as if he's absolutely convinced he's right. Apparently, some folks find that tone off-putting, but the fact of the matter is that he's passionate, he's blunt, and he is usually right. Joel is someone who has to be taken as a complete package. When you hear him speak, he speaks his mind and he speaks his truth; his tone is passionate, and with that passion comes an authority of opinion. One sees upon meeting him, however, that surrounding that fire is a pure kindness. Joel Salatin is far and away one of the kindest souls I have ever met. His family and the folks that work with him are equally kind. Never had I experienced such hospitality, especially in a group: smiles, favors, and a general sense of absolute ease. I think that part of the kindness that exudes from Joel and everyone around him is a genuine respect for all living things. Joel calls himself a "caretaker of creation" and he takes that role unbelievably seriously. Joel understands the place of every blade of grass, flower, worm, maggot, bacteria, fungi, chicken, cow, tree, newt, dog, rabbit, corn, bean, bee, pig, and person on his land and therefore respects each one in kind. He knows that no one thing can function without the other: without the maggots, the chickens would have one less thing to eat, without the chickens, his cows would get sick, without the cows, the fields would suffer and plants would die, worms couldn't eat without the cows or chickens and so they could not enrich the soil that feeds the cows and chickens, and then people couldn't eat either, and without the people who would do all this important work? Who would create these systems that mend the land, and without these 30 visitors, who would there be to continue the work? He sees humans as co-creators with God, who work not only to sustain the land and the life it supports, but to improve it, to regenerate it.

Joel says that he is "in the business of redemption." He really is. He spoke about ponds and how they "build forgiveness into the land." He's right. Nature is a hard and harsh place. Nature sends droughts and things wither and die as a result. But having ponds tides you, and all the wildlife and wild plants, over. Ponds soften the blows of nature, as does an abundance of organic matter in the soil, as does maintaining polycultures. Joel said that if we had invested the same resources we used to transform the plains into corn and soybeans into building thousands of ponds, we would have Eden. I think he might have a point.

I worry for those who shun the religious and spiritual language of Joel Salatin and farmers like him. I don't think there's a farmer out there who is doing good work and healing the land who is not moved to feel that he or she is somehow doing work that is connected to a higher order, that somehow sustains and redeems the spirit. In whatever guise you cast it, there is a something there when you do this work. Joel is bold enough to call it by its name.

I overheard him at supper one of the nights we were there say to someone ". . . the ecstasy of an angry farmer." I don't know what the context was, but that's Joel: his anger is a powerful, inflamed manifestation of absolute love; love so passionate that it transcends into ecstasy. And it is infectious love. You get a taste and suddenly it's all you can think about: getting more. For a week after I left Polyface I dreamed every night about Joel and his farm. I completely re-envisioned my own farm, adding new ideas into the mix, struggling with new understandings of what this work means, personally, politically, socially, ecologically, and everything else under the sun it touches. I felt that I could do so much more than I initially set out to do, that it was my responsibility to do more. I told Joel that the most important thing I learned with him was that it is okay to be bold. I think we live in a world that is too concerned with breaking the rules, especially when those rules don't make any sense. I think that as a girl I was taught, wittingly or unwittingly, too often to stand back, do as I was told, and to put my own thoughts aside; to abandon myself and my convictions. But such behavior does not benefit me or anyone else. Such thinking only ever allows things to stay the same. After I cam back from Polyface, I was moved to pick up my copy of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. The line, "do I dare disturb the universe" washed over me again and again. Prufrock, who is the epitome of inertia and the embodiment of inert creature that is the modern man can't bring himself to do anything for fear of it all. He is afraid of changing, of having any effect, of touching anything in the world around him and so he fails to do anything at all. It is the absolute opposite of Thoreau's plea "to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life."

(freshly killed chickens, served up for supper the following night)

Joel began the session with the slaughter of some 20 chickens that would be our supper the following night. Will such an act disturb the universe? I think so, but isn't that the point? I think he started there on purpose; to shake us, to wake us up to what this business of farming is really about, in case we had any doubts. Indeed, the day ended with a demonstration of rabbit breeding. In that blink of an eye, as the buck fell dramatically from the doe, I thought to myself, this is what we're here for: to protect, nurture, sustain, and participate in life (i.e. sex) and its destruction (i.e. death) which somehow sustains life. Joel knew we needed to be unabashedly disturbed into this realization: we are here for the express purpose of disturbing the universe. Anything else would be a wasted life.

(freshly killed chickens, served up for supper the following night)

Joel began the session with the slaughter of some 20 chickens that would be our supper the following night. Will such an act disturb the universe? I think so, but isn't that the point? I think he started there on purpose; to shake us, to wake us up to what this business of farming is really about, in case we had any doubts. Indeed, the day ended with a demonstration of rabbit breeding. In that blink of an eye, as the buck fell dramatically from the doe, I thought to myself, this is what we're here for: to protect, nurture, sustain, and participate in life (i.e. sex) and its destruction (i.e. death) which somehow sustains life. Joel knew we needed to be unabashedly disturbed into this realization: we are here for the express purpose of disturbing the universe. Anything else would be a wasted life.

(rabbits and chickens symbiotically cohabiting in the Ricken House)

Joel furthered this idea in more ways. Up in his woods, we sat and listened among his pigs, who roamed around paddocks tearing habitatingup brush and lolling in dirt: hog heaven. Joel showed us a 5-acre wood where he lets his pigs roam in the fall to hunt for acorns and root for tubers. He spoke of how in the old days, before Europeans came and the wild herds declined, animals would run through the woods, stamping out brush and scrap leaving room for the healthy trees and low grasses to take firm hold. He said how there were more forest fires then that furthered this cleaning out. He told us about how his pigs mimic this ancient process and that their disturbance of the woods one month of the year helped them to heal the other eleven. He told us that the idea that humans ought to keep their hands off nature was junk. It's true, he readily admits, that humans have done too much to disturb the natural order, but that we are an inherent part of the landscape, and how when we take up our rightful place, we can be not only be disturbers, but we can learn to use that disturbance, coupled with rest, to heal. Disturbance and rest could be Joel's motto, indeed it should be the motto of all grass farmers. That's the very principle of the thing: livestock eat the grass down a bit, tearing things up, and so long as they are not allowed to return to the same spot before it has recovered, the land, well, recovers. The rest the grass gets after being disturbed makes it grow back stronger, fuller, and healthier than before. You can take this idea and apply it to all kinds of things, not just farming. Joel, to the justifiably derisive laughter of a few women in the group, likened it to childbirth. He said, "what is childbirth if not a really big disturbance?!" one that brings about new life.

(rabbits and chickens symbiotically cohabiting in the Ricken House)

Joel furthered this idea in more ways. Up in his woods, we sat and listened among his pigs, who roamed around paddocks tearing habitatingup brush and lolling in dirt: hog heaven. Joel showed us a 5-acre wood where he lets his pigs roam in the fall to hunt for acorns and root for tubers. He spoke of how in the old days, before Europeans came and the wild herds declined, animals would run through the woods, stamping out brush and scrap leaving room for the healthy trees and low grasses to take firm hold. He said how there were more forest fires then that furthered this cleaning out. He told us about how his pigs mimic this ancient process and that their disturbance of the woods one month of the year helped them to heal the other eleven. He told us that the idea that humans ought to keep their hands off nature was junk. It's true, he readily admits, that humans have done too much to disturb the natural order, but that we are an inherent part of the landscape, and how when we take up our rightful place, we can be not only be disturbers, but we can learn to use that disturbance, coupled with rest, to heal. Disturbance and rest could be Joel's motto, indeed it should be the motto of all grass farmers. That's the very principle of the thing: livestock eat the grass down a bit, tearing things up, and so long as they are not allowed to return to the same spot before it has recovered, the land, well, recovers. The rest the grass gets after being disturbed makes it grow back stronger, fuller, and healthier than before. You can take this idea and apply it to all kinds of things, not just farming. Joel, to the justifiably derisive laughter of a few women in the group, likened it to childbirth. He said, "what is childbirth if not a really big disturbance?!" one that brings about new life.

New life is what Joel Salatin is about: creating life on his farm, breathing new life into the art and practice of farming, and he is a happy, happy man for it. The last thing Joel said to me before I left was this: "You will never regret self-abandonment." It shook me. I had just learned from Joel that one ought to be bold, that I should not ever stand back, do as I was told, or put my own thoughts aside; I must not abandon myself or my convictions. And yet, here was this assertion, this advice, this wisdom: "You will never regret self-abandonment." Self-abandonment is to do just that, to abandon one's self, one's power, position, rights, desires, ambitions; to give up to the control or discretion of another; to leave to one's disposal or mercy; to yield, cede, or surrender absolutely a thing to a person or agent. Surrender. Lines from Eliot's The Waste Land rolled through me: "The awful daring of a moment’s surrender." "You will never regret self-abandonment." It brought me to tears as I rode home.

Then spoke the thunder

D A

Datta: what have we given?

My friend, blood shaking my heart

The awful daring of a moment's surrender

Which an age of prudence can never retract

By this, and this only, we have existed

Which is not to be found in our obituaries

Or in memories draped by the beneficent spider

Or under seals broken by the lean solicitor

In our empty rooms

D A

Dayadhvam: I have heard the key

Turn in the door once and turn once only

We think of the key, each in his prison

Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison

Only at nightfall, aetherial rumours

Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus

D A

Damyata: The boat responded

Gaily, to the hand expert with sail and oar

The sea was calm, your heart would have responded

Gaily, when invited, beating obedient

To controlling hands. . .

(A hillside with pastured poultry houses fanning up it. Notice the fence line between

Joel's property and his neighbor's. The grass is indeed greener on this side.)

(A hillside with pastured poultry houses fanning up it. Notice the fence line between

Joel's property and his neighbor's. The grass is indeed greener on this side.)

I don't even really know where to begin as I write this. Perhaps the beginning is best. In March, Ross and I attended the Georgia Organics annual conference. It was an amazing event filled with workshops, networking sessions, fantastic food, and Michael Pollan as the keynote speaker. All and all it was a very stimulating weekend, however, the most important information I got while there was a bit of advice from

I don't even really know where to begin as I write this. Perhaps the beginning is best. In March, Ross and I attended the Georgia Organics annual conference. It was an amazing event filled with workshops, networking sessions, fantastic food, and Michael Pollan as the keynote speaker. All and all it was a very stimulating weekend, however, the most important information I got while there was a bit of advice from  (eggmobiles in action)

(eggmobiles in action) (Joel's herd)

So, long story short, we took Mr. Stoltzfoos' advice we went for a visit.

(Joel's herd)

So, long story short, we took Mr. Stoltzfoos' advice we went for a visit.  (freshly killed chickens, served up for supper the following night)

Joel began the session with the slaughter of some 20 chickens that would be our supper the following night. Will such an act disturb the universe? I think so, but isn't that the point? I think he started there on purpose; to shake us, to wake us up to what this business of farming is really about, in case we had any doubts. Indeed, the day ended with a demonstration of rabbit breeding. In that blink of an eye, as the buck fell dramatically from the doe, I thought to myself, this is what we're here for: to protect, nurture, sustain, and participate in life (i.e. sex) and its destruction (i.e. death) which somehow sustains life. Joel knew we needed to be unabashedly disturbed into this realization: we are here for the express purpose of disturbing the universe. Anything else would be a

(freshly killed chickens, served up for supper the following night)

Joel began the session with the slaughter of some 20 chickens that would be our supper the following night. Will such an act disturb the universe? I think so, but isn't that the point? I think he started there on purpose; to shake us, to wake us up to what this business of farming is really about, in case we had any doubts. Indeed, the day ended with a demonstration of rabbit breeding. In that blink of an eye, as the buck fell dramatically from the doe, I thought to myself, this is what we're here for: to protect, nurture, sustain, and participate in life (i.e. sex) and its destruction (i.e. death) which somehow sustains life. Joel knew we needed to be unabashedly disturbed into this realization: we are here for the express purpose of disturbing the universe. Anything else would be a  (rabbits and chickens symbiotically cohabiting in the Ricken House)

Joel furthered this idea in more ways. Up in his woods, we sat and listened among his pigs, who roamed around paddocks tearing habitatingup brush and lolling in dirt: hog heaven. Joel showed us a 5-acre wood where he lets his pigs roam in the fall to hunt for acorns and root for tubers. He spoke of how in the old days, before Europeans came and the wild herds declined, animals would run through the woods, stamping out brush and scrap leaving room for the healthy trees and low grasses to take firm hold. He said how there were more forest fires then that furthered this cleaning out. He told us about how his pigs mimic this ancient process and that their disturbance of the woods one month of the year helped them to heal the other eleven. He told us that the idea that humans ought to keep their hands off nature was junk. It's true, he readily admits, that humans have done too much to disturb the natural order, but that we are an inherent part of the landscape, and how when we take up our rightful place, we can be not only be disturbers, but we can learn to use that disturbance, coupled with rest, to heal. Disturbance and rest could be Joel's motto, indeed it should be the motto of all grass farmers. That's the very principle of the thing: livestock eat the grass down a bit, tearing things up, and so long as they are not allowed to return to the same spot before it has recovered, the land, well, recovers. The rest the grass gets after being disturbed makes it grow back stronger, fuller, and healthier than before. You can take this idea and apply it to all kinds of things, not just farming. Joel, to the justifiably derisive laughter of a few women in the group, likened it to childbirth. He said, "what is childbirth if not a really big disturbance?!" one that brings about new life.

(rabbits and chickens symbiotically cohabiting in the Ricken House)

Joel furthered this idea in more ways. Up in his woods, we sat and listened among his pigs, who roamed around paddocks tearing habitatingup brush and lolling in dirt: hog heaven. Joel showed us a 5-acre wood where he lets his pigs roam in the fall to hunt for acorns and root for tubers. He spoke of how in the old days, before Europeans came and the wild herds declined, animals would run through the woods, stamping out brush and scrap leaving room for the healthy trees and low grasses to take firm hold. He said how there were more forest fires then that furthered this cleaning out. He told us about how his pigs mimic this ancient process and that their disturbance of the woods one month of the year helped them to heal the other eleven. He told us that the idea that humans ought to keep their hands off nature was junk. It's true, he readily admits, that humans have done too much to disturb the natural order, but that we are an inherent part of the landscape, and how when we take up our rightful place, we can be not only be disturbers, but we can learn to use that disturbance, coupled with rest, to heal. Disturbance and rest could be Joel's motto, indeed it should be the motto of all grass farmers. That's the very principle of the thing: livestock eat the grass down a bit, tearing things up, and so long as they are not allowed to return to the same spot before it has recovered, the land, well, recovers. The rest the grass gets after being disturbed makes it grow back stronger, fuller, and healthier than before. You can take this idea and apply it to all kinds of things, not just farming. Joel, to the justifiably derisive laughter of a few women in the group, likened it to childbirth. He said, "what is childbirth if not a really big disturbance?!" one that brings about new life.

(A hillside with pastured poultry houses fanning up it. Notice the fence line between

Joel's property and his neighbor's. The grass is indeed greener on this side.)

(A hillside with pastured poultry houses fanning up it. Notice the fence line between

Joel's property and his neighbor's. The grass is indeed greener on this side.) Ross and I are up at VIAC this week finishing up some cheese chemistry courses. We took a most welcome field trip after class today to the beautiful

Ross and I are up at VIAC this week finishing up some cheese chemistry courses. We took a most welcome field trip after class today to the beautiful  The Farm itself sits on 1,400 acres of Vanderbilt family land. It is committed to farm and education programmes that encourage sustainable agriculture, and according to their website, they aim, "to cultivate a conservation ethic in students, educators and families who come here to learn." Right up my ally. We went to meet their cheesemaker, Nat Bacon, and to see their facility. They milk 125

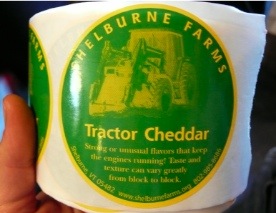

The Farm itself sits on 1,400 acres of Vanderbilt family land. It is committed to farm and education programmes that encourage sustainable agriculture, and according to their website, they aim, "to cultivate a conservation ethic in students, educators and families who come here to learn." Right up my ally. We went to meet their cheesemaker, Nat Bacon, and to see their facility. They milk 125  The label reads: Strong or unusual flavors that keep engines running! Taste and texture can vary greatly from block to block. The engine this cheese keeps running is the economic engine of the farm! This label demonstrates exactly how you sell your "mistakes" so as not to waste them. Sure, it's not going to win any prizes, but chances are that somebody out there likes your funky cheese, so why not keep the wheels of your operation turning as much when you fail as when you succeed? It's an interesting idea.

The label reads: Strong or unusual flavors that keep engines running! Taste and texture can vary greatly from block to block. The engine this cheese keeps running is the economic engine of the farm! This label demonstrates exactly how you sell your "mistakes" so as not to waste them. Sure, it's not going to win any prizes, but chances are that somebody out there likes your funky cheese, so why not keep the wheels of your operation turning as much when you fail as when you succeed? It's an interesting idea.

It's been seven, count them, seven months since I last wrote anything of substance. Inexcusable, I know. Especially when you consider how seven months ago I wrote the words, "You all will be hearing a great deal more about my teaching adventures in coming posts (which will be much more regular, henceforth)." Ha! But remember what else I said seven months ago, about how we're finding our way? Well, over the past seven months the way is finding its shape in some pretty awesome ways. We are shaping what we want to do with our lives here. It's no small potatoes and these things take time. Ross and I have been some incredibly busy bees with big, bright plans. Let's dive in, shall we?

It's been seven, count them, seven months since I last wrote anything of substance. Inexcusable, I know. Especially when you consider how seven months ago I wrote the words, "You all will be hearing a great deal more about my teaching adventures in coming posts (which will be much more regular, henceforth)." Ha! But remember what else I said seven months ago, about how we're finding our way? Well, over the past seven months the way is finding its shape in some pretty awesome ways. We are shaping what we want to do with our lives here. It's no small potatoes and these things take time. Ross and I have been some incredibly busy bees with big, bright plans. Let's dive in, shall we? Spring is coming, if you're quiet, you can hear the sun in the soil. . . shhhh. . . we walked through a grove of pink lady slippers today. . . we're eating herb salad and green cake. . . things are happening. . . more, very, very soon. . .

Spring is coming, if you're quiet, you can hear the sun in the soil. . . shhhh. . . we walked through a grove of pink lady slippers today. . . we're eating herb salad and green cake. . . things are happening. . . more, very, very soon. . .