If you're wondering why you may not have heard from us for a while, why we don't seem able to return phone calls, answer e-mails, remember birthdays or generally what day of the week it is, or recall if our underwear is right-side-out, there is only one thing to blame: THE HOUSE. It is the great culprit that has been stealing of all our time, energy, health, and sanity. It is best to begin at the beginning.When we first took this job, part of the agreement was that Spring House Meats would provide our housing. A few weeks before we were scheduled to begin work, we went up to the farm to figure out our housing options. At first, we thought we would live in a house on the hill with our fellow farmer, Erin Kirley, but another house had become available. Malanyon, who had worked on the farm for some time, decided to move on, so the house he had been occupying could be ours. Great, I thought. We went to look at it. What we saw would have sent any sane person running. At first impression, the exterior of the house looked cute: a typical well-worn, maybe even care-worn, little old farmhouse. The interior, however, was less forgiving. The word squalor comes to mind or maybe something stronger, a word that could strike at the very essence of filth. The disrepair was beyond words. The "living" room was blanketed in rat droppings that crunched like gravel under our feet. The metal sink and shelves in the kitchen were rusted, and rats had pilfered through every cabinet leaving plentiful evidence. Many long, thick snake skins decorated every crevice in the ceiling. Red wax dribbled down the walls in places. Unholy black dust fell like atomic snow from cracks in the ceilings and could be found behind every floorboard. The wood stove had been used as a trash can, filled with chip bags and coke cans and, as we later saw, a half-burned pair of men's underwear. You shouldn't be surprised at this point, but parts of the ceiling were rotted through. The floor in the kitchen could have been a trampoline. Window panes were missing and would fall out at the lightest touch, and spiders ruled the four corners of every room. Some insane person had put, and by "put" I mean nailed and stapled, greenish-yellow shag carpeting in the kitchen, where Malanyon had left peanut butter and canola oil open for God knows how long. The house looked as if its occupant had been abducted mid-way through making a sandwich. What was our response when we saw all this? "Great! Oh, this will be great, sure, we can do this, it's cute, it's got potential, it's just dirty, sure Jamie, we can clean this up. We can knock this out in two or three weeks!" Oh, oh, the naïvety! It's almost painful. No, it is painful. Call it excitement or blind enthusiasm, for blind it was. The fact of the matter is, we were out of our effing minds.Fortunately, Amy had Malanyon do the initial clean-up. When we got to work on the house, the rat-droppings were gone, the carpeting ripped up, and all of the appliances were removed except for the fridge. The pictures here begin with the house as it was when we started working. Sadly, or perhaps blessedly, all record of the way the house first looked is lost. We began with bleach. Lots and lots of bleach. Then, demolition. We tore out everything we could. Sheetrock, flooring, cabinets; did I mention we were insane to do this? When the carpeting was pulled out we found two layers of pre- World War Two linoleum underneath in various states of decay. We did well ripping it out with our gloved hands and respirators (asbestos is fun!) but we eventually had to go at it with a shovel. We found that the windows were not so much "installed" as they were "set" in their rough openings and held there by the trim. We tore out the mouldy sheetrock in the bedroom to find lovely beadboard walls, but they were so full of cracks and holes that no amount of wood epoxy could repair them. It should also be mentioned that the primary problem with the house is the fact that it does not have a true foundation. "A ship of ancient beams on a sea of moving stone" is how Ross describes the problems. Typical of the period the house was constructed, the foundation is pier and piling, which are wood beams and stone piles set on the ground. Trouble is, after about 100 years the ground and thus the stone and wood tend to move around a bit. The floor of the house is a visible arc. If you are in the bedroom you have to walk uphill to get to the living room. If you're in the living room you go downhill to the kitchen. As a result of all this pushing and pulling walls have separated from each other and from the ceiling and floorboards have pulled apart. All these factors plus no insulation rendered the house a sieve. So, in the process of filling in as many holes as possible with the amazing wonderful thing that is Great Stuff, we insulated. How, you might ask, does one insulate into walls that already exist without tearing them down? Why, with a hole-saw drill-bit, a rented insulation machine from Home Depot, duct tape, the top of a water bottle and lots and lots of cellulose. Insulating the house is a good example of what just about every day of housework was like.It begins with a trip to Home Depot. We probably spent a total of 30+ hours over the past two months inside Home Depot. Ross went to rent the 200lb insulation machine and purchase insulation, I went to get other things we needed for other projects: Rustoleum, masking tape, duct tape, drywall screws, etc. An hour later, we loaded the machine and everything else into the back of Jamie's truck and drive back to the farm. By now it is about 10am. We look around the house and see that part of the wall needs to be shorn up before we can start drilling into it. Then we discuss the relative merits of putting a vapour barrier up before we re-sheetrock. Then we get a phone call that the pigs have gotten out and help is needed to herd them back in and fix the fence. It is now 2:00 in the afternoon. We stop because we are both starving and drive to Trout Lily to pick up a sandwich. We set up the insulation machine after we call Home Depot to let them know we will need the machine for an extra day. We find an empty water bottle, cut it in half, and affix it to the insulation machine hose with duct tape to use as a spigot between the hose and the hole in the wall. We drill the first hole. The beadboard gets stuck in the hole-saw drill bit and we cant get it out. We spend half-an-hour getting the wood out and deciding if we need to go get a new drill-bit. We decide not to and keep going. We stop because the insulation we are blowing in is blowing out the "naturally-formed" holes in the walls and ceilings. We duct tape them shut. We continue. We stop. There is a flow problem in the hose and air is blowing but no insulation is coming. We spend an hour with the hose, a flashlight and a metal yardstick loosening the insulation so that it flows again. It is now 6:30pm and we have to stop. Only one wall is completed. Everything. I mean EVERYTHING, we did to this house went like this. Nothing was simple or straightforward, nothing could be done right the first time, nothing could be done right efficiently. One-hundred years of neglect and "git-er-done" attitude had taken its toll on this house to its very core; we fought back tooth and nail, blood, sweat, and tears. I couldn't begin to document and discuss every task we tackled on this house, but I took pictures of quite a lot of it, which is as good a way as any of showing you what we did.

Here is the house as it was when we started working:

The brightest room in the house, The Living Room

And the Bedroom

Notice the thick layer of grime all over everything. Let’s move on to the demolition. Here is the bedroom again:While Ross and Clay tore out a lot of this sheetrock, I spent the day working on the kitchen sink. The sink had not been cleaned. It was still covered in rat feces that had to be Shop Vac'd out before we could take it out of the house. It’s a really old, beautiful, retro metal sink, but it was so rusty and nasty. Armed with gloves, tarp, a respirator, a steel-brush, and about 7 cans of rustolium, in 7 hours, I restored it:

On another day, we got up under the house to check things out. Only, we couldn’t because there was about $90 worth of scrap metal in the form of old farm equipment parts, chairs, and a pair of shoes under there.

After most of the demolition was completed, we started insulating and putting things back together. Here is the old, filled-in fireplace. We removed the mantle from the old, filled-in fireplace and pulled out some of the rotten sheetrock. Now, generally, sheetrocking is something that, once you know how to do it, it’s pretty easy. Not so here. This house slopes. It slopes a lot. The ceiling sags. Each. Tedious. Individual. Piece. Of. Sheetrock. Had. To. Be. Custom. Cut. And. Measured. Within. One-quarter. Inch. Then mudded and taped. Then primed. Twice. Then painted. Twice. And that’s just the walls.One night, Tim and Clay came by to help out. The four of us were consumed with replacing the fixtures in the shower. It required copious amounts of sawing, lots of hair pulling, and about 4 hours: just to remove the old fixture! (picture)On one occasion, coming home from Home Depot with floor and ceiling trim in the back of the truck, the wood chewed through the polytwine and $60 flew out the back of the truck and can still be seen (update: a state convict crew has removed the wreckage) in all its many bits and pieces on where 74-A intersects with I-40. Shall I go on? The glazing on the windows was crumbling away or gone completely. Ross and I stood outside for hours in the cold wind and snow on top of a ladder putting sub-zero window glaze and new panes in. We masked and painted every wall and ceiling we could get our hands on. We tore out all the kitchen cabinets. We went to Ikea and spent a week rebuilding and installing new ones. We bevel-cut trim and hung it. We replaced rotten floorboards. We put in two new windows. We used expanding foam everywhere. Ross spent two days under the house rewiring in a crawl-space that over half of is too short to even belly-crawl into. We put in new plugs and light fixtures. Then, after all that, we had to move in. Actually, we had to move in before the house was done, which is a whole other story. . .We should have torn the whole thing down and started afresh.The thing to know, to really keep in mind about renovation is that you may have what looks like a very reasonable list of things to accomplish, but you may never get past the first task. You need, as my mother’s favourite piece of Engrish from an instruction booklet suggests, to “get some people to help you.” Or, as the epigraph on one of the renovation books we used states (or perhaps cautions) the old adage, “Many hands make work light.” But in our case, many hands we seldom if ever (forgive me) on hand. And so, after many weeks and several months, the house became what it is today. It is as if it feebly approached the “charm” I had hoped for —and then gave up. It is way below our normal, acceptable standard of living, and constantly dances the line between habitable and uninhabitable. I cannot imagine the house without insulation as I watch little bits of grey cellulose blow in onto my bedside table from where the house is separating from itself. We are making do, which sometimes, is all you can do.My hope is that this house is in no way a foreshadowing of our future as farmers. What I mean is this: after lots of thought, it has occurred to me that in our aspirations to become outstanding farmers, we may have bitten off more than we can chew; there may not be enough people to help along the way, and the end-product may be less than satisfying. But then, the reality becomes clear: this house does not have to foreshadow anything so long as it is a source of learning. Ross and I now both know what it takes to change something that is

both old and broken. We know just how much work it can be and we know what it demands of us. We may yet be able to change the practice of farming, but mark my words: we will never renovate again.

When I was visiting

When I was visiting

I harvested my garden's first melon this week. It was perfect. This recipe is a bit of a mutt. It was inspired by a desert served at the CSA Members Potluck Saturday of blueberries, melon, and mint, mingled with a few ideas lifted out of Star Provisions' peach and mint salad. I was pretty pleased with the results. I know you're thinking "pepper and fruit?" but go with me here. The mint and lime make it refreshing and cool while the black pepper balances it all out by paying a kind of homage to summer's heat:

I harvested my garden's first melon this week. It was perfect. This recipe is a bit of a mutt. It was inspired by a desert served at the CSA Members Potluck Saturday of blueberries, melon, and mint, mingled with a few ideas lifted out of Star Provisions' peach and mint salad. I was pretty pleased with the results. I know you're thinking "pepper and fruit?" but go with me here. The mint and lime make it refreshing and cool while the black pepper balances it all out by paying a kind of homage to summer's heat: and,

and,

Ross and I are up at VIAC this week finishing up some cheese chemistry courses. We took a most welcome field trip after class today to the beautiful

Ross and I are up at VIAC this week finishing up some cheese chemistry courses. We took a most welcome field trip after class today to the beautiful  The Farm itself sits on 1,400 acres of Vanderbilt family land. It is committed to farm and education programmes that encourage sustainable agriculture, and according to their website, they aim, "to cultivate a conservation ethic in students, educators and families who come here to learn." Right up my ally. We went to meet their cheesemaker, Nat Bacon, and to see their facility. They milk 125

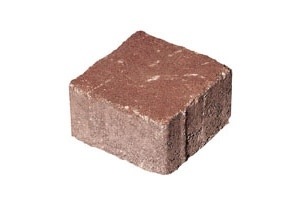

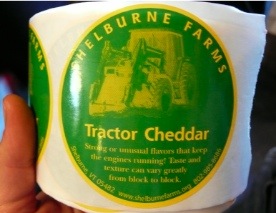

The Farm itself sits on 1,400 acres of Vanderbilt family land. It is committed to farm and education programmes that encourage sustainable agriculture, and according to their website, they aim, "to cultivate a conservation ethic in students, educators and families who come here to learn." Right up my ally. We went to meet their cheesemaker, Nat Bacon, and to see their facility. They milk 125  The label reads: Strong or unusual flavors that keep engines running! Taste and texture can vary greatly from block to block. The engine this cheese keeps running is the economic engine of the farm! This label demonstrates exactly how you sell your "mistakes" so as not to waste them. Sure, it's not going to win any prizes, but chances are that somebody out there likes your funky cheese, so why not keep the wheels of your operation turning as much when you fail as when you succeed? It's an interesting idea.

The label reads: Strong or unusual flavors that keep engines running! Taste and texture can vary greatly from block to block. The engine this cheese keeps running is the economic engine of the farm! This label demonstrates exactly how you sell your "mistakes" so as not to waste them. Sure, it's not going to win any prizes, but chances are that somebody out there likes your funky cheese, so why not keep the wheels of your operation turning as much when you fail as when you succeed? It's an interesting idea.

So, I haven't had a garden since I left my parents' home some eight years ago. D'avignon radishes were my first harvest from my new garden, my new house, my new life. Small, delicate, sweet, crisp, spicy, just wonderful. I put a jar up to savour this ephemeral and long-awaited moment.

So, I haven't had a garden since I left my parents' home some eight years ago. D'avignon radishes were my first harvest from my new garden, my new house, my new life. Small, delicate, sweet, crisp, spicy, just wonderful. I put a jar up to savour this ephemeral and long-awaited moment. For those who want to know how to put up radishes: just slice the radishes however you like, heat enough vinegar to fill the jar (I used white distilled, but you could use apple cider or rice vinegar) and about 1/4 cup of sugar, or until you just begin to taste it. I also dropped in a bay leaf, just because it seemed like a good idea. Heat the vinegar until the sugar dissolves and pour into a hot, sterilized jar. Seal according to the manufacturer's instructions. The vinegar-sugar solution should turn this gorgeous pale pink. Let sit in a cool, dry place until you feel like eating them (at least 2 weeks).

For those who want to know how to put up radishes: just slice the radishes however you like, heat enough vinegar to fill the jar (I used white distilled, but you could use apple cider or rice vinegar) and about 1/4 cup of sugar, or until you just begin to taste it. I also dropped in a bay leaf, just because it seemed like a good idea. Heat the vinegar until the sugar dissolves and pour into a hot, sterilized jar. Seal according to the manufacturer's instructions. The vinegar-sugar solution should turn this gorgeous pale pink. Let sit in a cool, dry place until you feel like eating them (at least 2 weeks).

It's been seven, count them, seven months since I last wrote anything of substance. Inexcusable, I know. Especially when you consider how seven months ago I wrote the words, "You all will be hearing a great deal more about my teaching adventures in coming posts (which will be much more regular, henceforth)." Ha! But remember what else I said seven months ago, about how we're finding our way? Well, over the past seven months the way is finding its shape in some pretty awesome ways. We are shaping what we want to do with our lives here. It's no small potatoes and these things take time. Ross and I have been some incredibly busy bees with big, bright plans. Let's dive in, shall we?

It's been seven, count them, seven months since I last wrote anything of substance. Inexcusable, I know. Especially when you consider how seven months ago I wrote the words, "You all will be hearing a great deal more about my teaching adventures in coming posts (which will be much more regular, henceforth)." Ha! But remember what else I said seven months ago, about how we're finding our way? Well, over the past seven months the way is finding its shape in some pretty awesome ways. We are shaping what we want to do with our lives here. It's no small potatoes and these things take time. Ross and I have been some incredibly busy bees with big, bright plans. Let's dive in, shall we? Spring is coming, if you're quiet, you can hear the sun in the soil. . . shhhh. . . we walked through a grove of pink lady slippers today. . . we're eating herb salad and green cake. . . things are happening. . . more, very, very soon. . .

Spring is coming, if you're quiet, you can hear the sun in the soil. . . shhhh. . . we walked through a grove of pink lady slippers today. . . we're eating herb salad and green cake. . . things are happening. . . more, very, very soon. . .